Syria’s Reconstruction: A Blueprint for the Many, Not the Few

For generations, Ahmad’s family tended their olive grove on a sun-drenched hill in Syria. The trees were their inheritance and their future, a symbol of peace and permanence. Then the war came and turned it all to ash. Today, Ahmad’s dream isn’t just to replant his trees; it’s to rebuild a life. But he knows that after the bombs stop, a different kind of war often begins, a war fought with contracts and capital.

Ahmad’s story is Syria’s story. As the world talks of a $400 billion reconstruction, the crucial question is this: will the recovery be for people like Ahmad, or will it become a second catastrophe? Too often, “reconstruction” becomes a period of predatory extraction, where international corporations and local strongmen carve up the spoils, leaving ordinary people with nothing but deeper debts and shattered hopes.

We’ve seen this tragic story play out before.

In Lebanon, a small group of political and business elites bulldozed historic Beirut to build luxury towers, enriching themselves while burying the country under a mountain of debt.

In Afghanistan, billions in aid vanished into a “ghost economy” of phantom schools and non-existent projects, funding the lavish lifestyles of the powerful while a generation was left behind.

After the 2004 tsunami in Indonesia, a flood of “impatient capital” overwhelmed weak accountability systems, allowing the well-connected to capture vast sums while thousands of families languished in tents.

These aren’t just isolated mistakes. They are the predictable results of a broken model.

Now, Syria stands at the same perilous crossroads. As I argue in my book, Rewriting the Rules: A Vision for Syria’s Sustainable Reconstruction, the country’s near-total destruction has created a tragic but unique opportunity: a “blank slate.” This is a chance to design a new kind of recovery, one that doesn’t just rebuild what was lost, but builds something better for Ahmad and millions like him. This model is built on a simple, powerful idea: Financial Self-Determination.

Why Does Reconstruction So Often Fail?

To build a better future, we first have to understand why past efforts have failed so spectacularly. The mechanics of failure are surprisingly consistent. The playbook for failure rests on three toxic pillars: elite capture, “impatient capital,” and a vacuum of good governance.

1. The Architecture of Elite Capture This isn’t random corruption; it’s the system itself being weaponized for private gain. In Lebanon, a single private company, controlled by the prime minister, was given the keys to Beirut’s reconstruction, turning public assets into private fortunes. In Afghanistan, it was a more diffuse network, a “criminalised marketplace” where political, military, and business elites used institutions like Kabul Bank to systematically siphon off aid money.

2. The Peril of “Impatient Capital” When billions of dollars in aid pour into a fragile country, there is immense pressure to spend it fast. This “impatient capital” bypasses the very checks and balances designed to prevent corruption. In the rush to show results, money ends up in the wrong pockets, and the people who need it most are forgotten.

3. The Governance Vacuum This is the ingredient that makes it all possible. Without transparent, accountable, and independent institutions, there is nothing to stop the feeding frenzy. Corruption becomes the norm, and the state, which should serve the people, instead serves the predators.

A New Compass: Building a Future That Puts People and Planet First

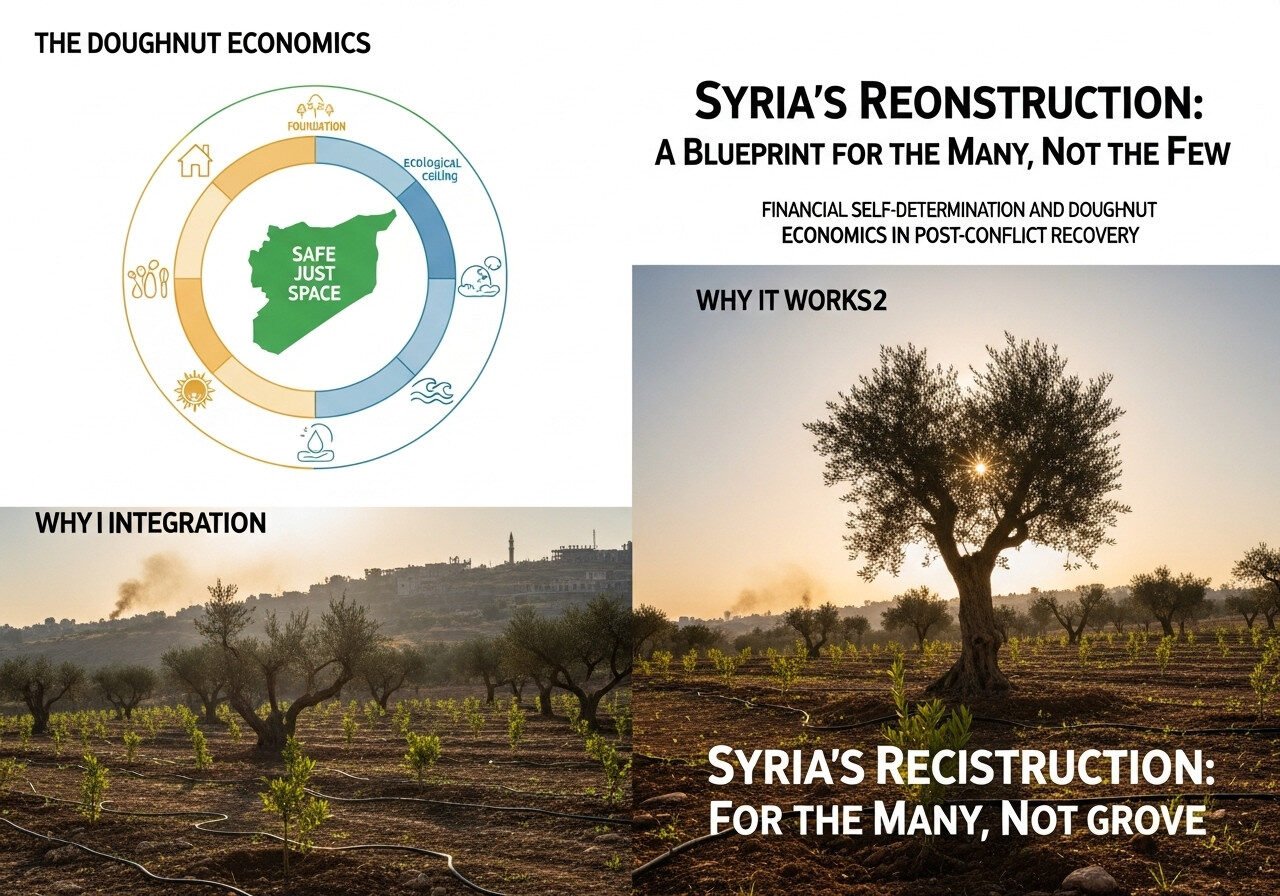

To avoid these traps, Syria needs more than a new map; it needs a new compass. That compass is Kate Raworth’s “Doughnut Economics.“

It’s a simple idea with profound implications. Instead of chasing endless GDP growth, the goal is to create a “safe and just space for humanity.” Think of it like a doughnut:

The inner ring is the social foundation. It’s the absolute minimum everyone needs for a dignified life: food, clean water, housing, energy, healthcare, education. No one should fall through this floor.

The outer ring is the ecological ceiling. These are the planet’s boundaries, like a stable climate and healthy oceans, that we cannot cross without causing irreversible harm.

For Syria, this isn’t an abstract theory. It means setting concrete goals: building energy-efficient homes for the millions displaced, creating food systems that can withstand drought, and powering the nation with decentralised, community-owned renewable energy. It means rebuilding the economy to be three times larger, while keeping carbon emissions below pre-war levels.

Because of its “blank slate” status, Syria has a unique chance to embed these principles into its DNA from day one, rather than trying to retrofit them onto a broken, 20th-century system.

Four Keys to Unlock a Better Future

So how do you connect this vision to the global capital needed to make it real? The model of Financial Self-Determination is built on four pillars, each designed as a direct countermeasure to the failures of the past.

1. Mandate Local Ownership The wealth generated in Syria must stay in Syria. Through legally binding Community Benefit Agreements (CBAs), a percentage of all project profits would go directly into funds managed by local communities. This ensures Syrians are the primary builders, and beneficiaries, of their own future.

2. Control Profit Repatriation This is about ensuring partnership, not plunder. Investment contracts would include clauses requiring foreign companies to reinvest a large portion of their profits back into the Syrian economy for a set number of years. This prevents what could be called “carbon colonialism.” This is a modern form of exploitation where, for example, a foreign company could lease vast tracts of Syrian land for a reforestation project. The company would then earn millions by selling “carbon credits” on international markets, credits generated by the new forests. Without the right protections, all those profits could be sent home, leaving Syria with a green project it doesn’t control and from which its people gain little more than low-wage jobs.

3. Enforce Radical Transparency Sunlight is the most powerful disinfectant. A public digital portal would disclose every major reconstruction contract in real-time, including, crucially, the beneficial owners of the companies involved. The “ghost school” fraud of Afghanistan is impossible when any citizen with a smartphone can see exactly who was paid, how much, and for what.

4. Build Negotiating Capacity A fragile state cannot be expected to go head-to-head with the army of lawyers and financiers from a multinational corporation. A National Negotiation Support Unit, staffed by world-class Syrian experts, would ensure the nation’s interests are fiercely protected in every deal, preventing it from being locked into exploitative contracts.

| Metric | The Broken Model | The Syrian Blueprint |

Capital | Conditional Loans, Aid | ESG Investment, Green Bonds |

Actors | Foreign Contractors, Elites | Local Communities, Syrian Diaspora |

Benefits | Captured by the Few | Shared via Community Agreements |

Transparency | Opaque, After-the-Fact | Real-time, Proactive |

Outcome | Debt and Dependency | Self-Determination |

Conclusion: A Choice for Ahmad, A Test for the World

A sophisticated financial plan is useless without a trustworthy state to run it. Here again, tragedy offers an opportunity: Syria can build digital-first, transparent-by-default institutions from scratch, leapfrogging the opaque systems where corruption thrives.

For Ahmad, standing on his barren land, this isn’t an abstract policy debate. It’s his life. The choice is between three starkly different futures:

The Conventional Path: A foreign-led project seizes his land for a large-scale agro-business, offering him a low-wage job on the land his family owned for centuries. The profits flow overseas.

The Failed State: He never gets to replant. The land remains scorched as new conflicts erupt over scarce resources, and his hope for a future turns to dust.

The Transformational Leapfrog: His village co-operative uses funds from a Community Benefit Agreement to build a solar-powered irrigation system. He not only replants his ancient olive grove but registers it in a carbon-capture project, earning an income that helps his community thrive. He isn’t a victim of reconstruction; he is an architect of it.

Proving that a sustainable and equitable recovery can work, even in the most challenging environment on Earth, would create a powerful blueprint for a new era of post-conflict reconstruction. It would show that the ashes of war can, with courage and deliberate design, become the fertile ground for a future that benefits all.

The blueprint exists. The choice is whether we have the collective courage to build it, for Ahmad’s olive trees, and for all of Syria.