The Valuation of Resilience: Navigating the RICS Global Standards for ESG in Commercial Property

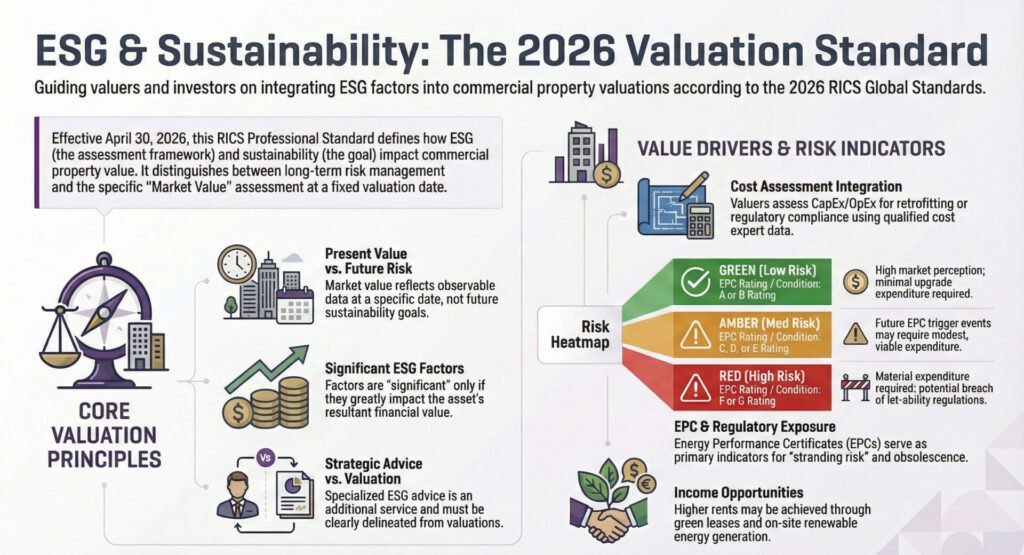

The inauguration of the Royal Institution of Chartered Surveyors (RICS) Professional Standard (4th edition) in January 2026 represents a seminal moment for global real estate capital markets, occurring at a time when a ‘wall of capital’ is increasingly scrutinising the sustainability credentials of underlying assets. Effective from 30 April 2026, this update signifies a formal transition from discretionary ESG (environmental, social, and governance) reporting to a mandatory, standardised framework integrated within the RICS Red Book Global Standards (RICS, 2026). For the institutional investor, this is far more than a technical adjustment; it is a regulatory pivot designed to mitigate systemic risk and enhance the transparency of asset pricing in a global economy where the cost of carbon is becoming as influential as the cost of debt.

Real estate, historically viewed through the lens of lease lengths and covenant strengths, is being fundamentally repriced. The governance of these new standards falls under the Standards and Regulation Board (SRB), which operates in the public interest to maintain the technical and ethical integrity of the profession. Within this framework, a critical distinction is made regarding the hierarchy of requirements: “must” denotes a mandatory obligation where any deviation constitutes a professional breach, while “should” indicates expected best practice where acceptable alternatives might exist (RICS, 2026). This linguistic precision ensures that the “valuation of resilience” is a rigorous, audit-ready process rather than a vague qualitative exercise. The intentional “implementation gap” between the January publication and the April effective date provides a brief window for firms to recalibrate their internal data gathering and risk assessment protocols to meet the new rigour.

The scope of the 4th edition is precisely tailored to commercial property: non-domestic real estate fulfilling operational or occupational purposes. While it excludes purely residential sectors and the granular complexities of development valuation (governed by separate standards), its global applicability creates a unified baseline for institutional capital. For mixed-use assets, the valuer is now required to apply these standards to the commercial elements through professional judgement. This standard serves as the connective tissue between high-level sustainability aspirations and the hard financial realities of asset valuation, compelling market participants to recognise that ESG factors are no longer externalities but intrinsic drivers of market value.

The Conceptual Divide: Present Market Value vs Future ESG Risk

A fundamental tension exists between the multi-decade horizon of sustainability goals and the “point-in-time” nature of a Red Book valuation. Market Value, as defined by the International Valuation Standards (IVS), is a snapshot of market sentiment at a specific date (IVSC, 2024). However, the ‘pricing lag’ between emerging climate risks and observed transaction data often creates a disconnect. This lag represents a significant idiosyncratic risk: the danger that an asset’s value may remain artificially buoyant until a regulatory or environmental ‘trigger event’, such as a sudden tightening of energy performance mandates, causes a sharp correction in liquidity. This phenomenon leads to the creation of ‘stranded assets’, properties that face functional obsolescence because the capital expenditure required to bring them up to modern ESG standards exceeds their potential to generate competitive returns in a bifurcated market.

To navigate this, the valuer must distinguish between “ESG Risk Analysis,” which focuses on long-term management and value resilience, and the “Valuation” itself, which must be anchored in measurable market evidence. The standard identifies five strategic reasons why ESG risks may not yet be reflected in a separate, explicit valuation adjustment. First, in prime markets, high-tier ESG performance is often synonymous with “Core” asset quality. These features are baked into the premium yield and cannot be meaningfully unbundled (RICS, 2026). Second, in many transactions, traditional drivers such as covenant strength, lease length, and location remain the dominant pricing factors, effectively masking the marginal impact of sustainability credentials.

Third, certain ESG initiatives, such as community engagement programmes, enhance an owner’s reputation but may not translate into the specific financial considerations that a “willing buyer” would pay for at the valuation date. Fourth, a risk may be theoretically significant (such as a 2050 net-zero target) but has not yet reached a level of maturity or proximity where it dictates current transaction prices in the open market. Finally, in mature jurisdictions, high sustainability performance is no longer a “bonus” but a baseline expectation. In such cases, value is impacted not by the presence of ESG features, but by their absence, leading to yield expansion for “brown” assets.

The distinction between “Market Value” and “Investment Value” remains paramount. While Market Value reflects the consensus of the “willing buyer and seller,” Investment Value accounts for a specific owner’s strategic objectives (IVSC, 2024). A valuer must resist the urge to incorporate a particular owner’s aggressive decarbonisation strategy into a Market Value assessment if the broader market does not yet share that appetite. To do so would risk an “aspirational valuation” that fails the test of market evidence and undermines the reliability of the Red Book.

Professional Boundaries: Distinguishing Valuation from Strategic Advice

The expansion of ESG requirements has heightened the risk of professional liability, particularly when valuers provide advice that strays into technical building physics or complex climate modelling. As institutional investors increasingly rely on valuation reports for disclosure under the TCFD (Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures), any perceived inaccuracy in ESG-related advice could trigger litigation. Consequently, the valuer must maintain a clear boundary between market-based reporting and the predictive, often speculative, nature of climate-resilience modelling. Strategic sustainability advice is an additional service, not a core component of a Red Book valuation. Providing such advice requires a specific set of competencies, often involving a synthesis of cost consultancy and environmental risk assessment that exceeds the typical valuer’s remit.

To mitigate these risks, the RICS standard mandates a strict linguistic and procedural separation between valuation reports and strategic consultancy (RICS, 2026). Strategic advice is often predictive or based on specific “what-if” scenarios, such as a transition risk assessment. If these two services provided by the same firm, they must be governed by separate terms of engagement to avoid the appearance of a conflict of interest or a breach of the RICS Rules of Conduct.

The standard provides a clear set of linguistic boundaries. Valuers and consultants must be disciplined in their terminology to ensure that qualitative strategic assessments are never confused with formal opinions of value. Terms such as “Market Value,” “Price,” and “Basis of Value” are reserved strictly for the valuation report. Conversely, strategic advice should utilise terms like “Assessment,” “Qualitative analysis,” and “Strategic projection” (RICS, 2026). This clarity is essential for institutional clients who must distinguish between a bankable valuation and a forward-looking risk management document.

The Economics of Transition: Capital and Operational Expenditure

The assessment of Capital Expenditure (CapEx) and Operational Expenditure (OpEx) is the most direct conduit through which ESG factors influence property value. As the ‘transition risk’ of the shift to a low-carbon economy accelerates, the cost of retrofitting assets to meet new legal requirements has become a primary driver of yield expansion for substandard assets. In an environment of elevated interest rates, the financing of these retrofits becomes significantly more expensive, further depressing the value of ‘brown’ buildings. Valuers must now consider whether a property’s projected rental growth can realistically offset the escalating cost of required energy-efficiency upgrades, or if the asset faces a structural decline in its capital value.

The standard establishes a clear mandate: valuers should typically rely on cost estimates from qualified construction professionals, such as quantity surveyors. The valuer’s role is that of a synthesiser, not an estimator. There are limited circumstances where a valuer may derive their own estimates, such as using published indices for generic, low-value assets, but this approach must be agreed upon in the terms of engagement and is generally considered less reliable (RICS, 2026).

Crucially, the valuer must act as a gatekeeper of data. Under the Red Book Global Standards, members must apply “professional scepticism” to all client-provided data (RICS, 2022). In a market where “greenwashing” presents a legal and reputational hazard, the valuer must scrutinise whether proposed ESG costs reflect actual pending legal requirements or merely the aspirational goals of the current owner. If the valuer identifies potential legal issues, such as a failure to meet energy efficiency deadlines, they must explicitly state that this information requires verification by legal advisors before the valuation can be fully relied upon. This gatekeeper role is essential for institutional risk management, ensuring that “green” premiums are supported by technical reality rather than marketing rhetoric.

The Evidence Gap: Comparable Evidence and Market KPIs

A persistent challenge in the valuation of resilient assets is the “evidence gap.” While IVS 103 requires valuers to make adjustments for ESG differences between subject assets and comparables, granular ESG data is notoriously difficult to extract from private transaction evidence (IVSC, 2024). Unlike lease terms or sale prices, energy intensity or physical risk mitigation measures are rarely disclosed in standard marketing particulars.

To bridge this gap, the standard requires a proactive approach to data gathering, benchmarking assets against a framework of globally recognised Key Performance Indicators (KPIs). These KPIs provide the necessary data points to justify adjustments in yield or rental growth projections.

KPI Category | Example Data / Reference | Unit of Measurement | Expected Market Relevance |

Energy Ratings | EPC or regional equivalents (e.g. NABERS) | Rating (A-G), $kWh/m^2$ | Regulatory exposure; required CapEx for upgrades |

Renewable Production | Solar PV, heat pumps, or geothermal | % of energy demand met | Energy security; potential for supplementary income |

Certifications | BREEAM, LEED, DGNB, or WELL | Level (e.g. Platinum) | Third-party verification; tenant attraction |

Physical Climate Risk | Flood, heat, or drought analysis (to 2050) | Yes/No; planned CapEx | Insurance availability; long-term location viability |

Mobility | EV charging points; bicycle spaces | Points per employee | Meeting modern occupier demands; future-proofing |

Water Usage | Consumption levels; saving measures | $m^3/year$; reuse details | Operational cost savings; resilience in stressed areas |

For comparable evidence to be acceptable under this standard, it must meet four rigorous criteria: it should be publicly available, require no specialist interpretation, be capable of supporting market analysis, and be capable of verification (RICS, 2026). The difficulty of obtaining such data in private markets (where transaction details are often shielded by non-disclosure agreements) remains a significant pain point for the profession. This opacity often forces valuers to rely on ‘sentiment-led’ adjustments rather than ‘evidence-led’ ones, a practice that the new standards seek to curtail. Where these criteria cannot be met, the valuer is professionally obligated to state the limitations and the explicit assumptions made, providing a clear audit trail for the client and protecting the valuer from charges of professional negligence should the market move against their assessment.

Jurisdictional Nuance: The EU, UK, and Australian Frameworks

While the RICS standard provides a global baseline, the maturity of regional regulatory frameworks creates a tiered landscape of risk. Valuers must augment the global approach with specific jurisdictional requirements to ensure that “Market Value” reflects local legal realities.

The European Union Layer

The European Union has moved faster than any other region to codify sustainable finance through the EU Taxonomy and the Sustainable Finance Disclosure Regulation (SFDR). The SFDR’s classification of products into Article 8 (promoting environmental or social characteristics) and Article 9 (with sustainable investment as an objective) has created a bifurcated market (European Commission, 2021). Capital is increasingly fleeing “brown” assets that do not meet the Taxonomy’s “climate contribution criteria,” such as an EPC class of at least A for buildings constructed before 2021 (European Commission, 2019). This is not just a reporting requirement: it is a driver of yield expansion for non-compliant assets, which face being “stranded” as institutional funds prioritise Taxonomy-aligned investments to avoid “greenwashing” accusations.

The United Kingdom Layer

In the United Kingdom, the primary levers of value are the Minimum Energy Efficiency Standards (MEES) and Energy Performance Certificates (EPCs). A critical, and often overlooked, detail is that registered exemptions from MEES only last for five years (UK Government, 2011). This creates a “valuation cliff” where an exempt asset may suddenly require material expenditure upon the exemption’s expiry. Valuers are encouraged to use a “Red/Amber/Green” risk rating to communicate this exposure. A “Green” rating implies an A or B rating or a property exempt with no material expenditure required. “Amber” denotes C, D, or E ratings, while “Red” signifies an F or G rating, or a known future rating of C-G where significant investment is imminent (RICS, 2026).

The Australian Layer

Australia’s framework, defined by NABERS and the Commercial Building Disclosure (CBD) programme, is increasingly focused on “embodied carbon” (Australian Government, 2022). While operational carbon remains vital, the NSW Sustainable Buildings SEPP 2022 introduces mandatory reporting of embodied carbon for all new developments (NSW Government, 2022). For the valuer, this creates a strategic distinction: new developments may command a “green premium” for their low-carbon construction, while existing stock may face “functional obsolescence” if it cannot be retrofitted to meet these emerging circular economy principles.

The Road Ahead: The Valuer as a Market Interpreter

The evolution of these standards reflects a broader shift in global capital. The valuer’s role is no longer merely to report on historical transactions, but to act as a precise interpreter of how sustainability influences market behaviour and financial resilience. By standardising the language and methodology of ESG, RICS ensures that the profession remains the arbiter of value in an era where climate risk is synonymous with financial risk.

The mandatory requirements of the 4th edition become effective on 30 April 2026. This deadline is a clarion call for the industry to move beyond qualitative “sustainability sections” in reports toward a rigorous, data-driven analysis of cost and risk. Ultimately, the valuation of resilience is about ensuring that the Market Value of today is calculated with a clear-eyed understanding of the regulatory and environmental realities of tomorrow. Those who fail to adapt to this new rigour risk not only professional censure but also the mispricing of the most significant asset class in the global economy.

References

Australian Government (2022) Commercial Building Disclosure (CBD) Program. Canberra: Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water, https://www.dcceew.gov.au/sites/default/files/documents/commercial-buildings-energy-consumption-baseline-study-2022.pdf

European Commission (2019) EU Taxonomy for Sustainable Activities. Brussels: European Union, https://finance.ec.europa.eu/system/files/2019-06/190618-sustainable-finance-teg-report-taxonomy_en.pdf

European Commission (2021) Sustainable Finance Disclosure Regulation (SFDR). Brussels: European Union, https://finance.ec.europa.eu/regulation-and-supervision/financial-services-legislation/implementing-and-delegated-acts/sustainable-finance-disclosures-regulation_en

International Valuation Standards Council (2024) International Valuation Standards (IVS). London: IVSC, https://ivsc.org/new-edition-of-the-international-valuation-standards-ivs-published/

NSW Government (2022) State Environmental Planning Policy (Sustainable Buildings) 2022. Sydney: NSW Department of Planning and Environment, https://legislation.nsw.gov.au/view/whole/html/inforce/current/epi-2022-0521

RICS (2022) RICS Valuation – Global Standards (The Red Book Global Standards). London: Royal Institution of Chartered Surveyors, https://www.rics.org/profession-standards/rics-standards-and-guidance/sector-standards/valuation-standards/red-book/red-book-global

RICS (2026) ESG and sustainability in commercial property valuation. 4th edn. London: Royal Institution of Chartered Surveyors, https://www.rics.org/content/dam/ricsglobal/documents/standards/esg-sustainability-commercial-valuation-4th-edition.pdf

UK Government (2011) Energy Act 2011 (MEES Regulations). London: The National Archives, https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/energy-act-2011