Syria’s Fiscal Dilemma Between Monetary Reform and Humanitarian Reconstruction (2025-2026)

The Macro-Humanitarian Nexus

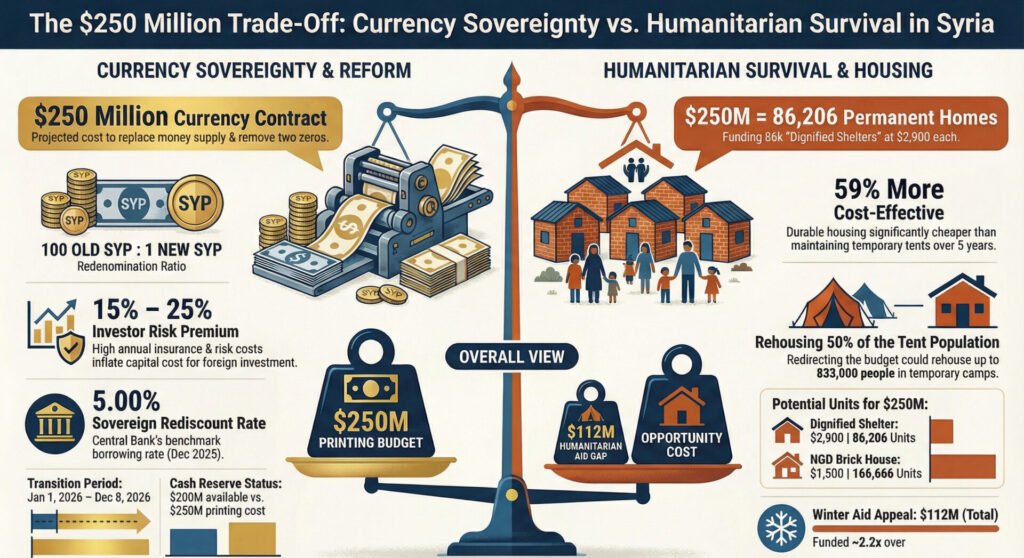

The abrupt collapse of the former regime in December 2024 served as the primary catalyst for a fundamental restructuring of Syria’s institutional and humanitarian landscape (House of Commons Library, 2026). Under the transitional administration of President Ahmad al-Sharaa, the state has entered a critical period defined by the dual necessity of establishing a viable sovereign monetary system and addressing a catastrophic housing deficit for millions of internally displaced persons (IDPs) (TRT World, 2026). As of early 2026, the central tension in Syrian fiscal policy remains the strategic allocation of restricted capital between the “New Syrian Pound” redenomination project and the transition of roughly two million individuals from temporary tents into durable, permanent housing in the northwest (AWS, 2025). This competition for liquid assets represents a high-stakes junction in the nation’s recovery, as the administration must navigate the complex trade-offs between symbolic sovereignty and immediate human survival.

The strategic importance of this dual-track recovery cannot be overstated: the fiscal decisions made throughout 2026 will fundamentally define the legitimacy of the new state in the eyes of both the international community and a weary domestic population (Modern Diplomacy, 2025). While the restoration of a stable currency is required to facilitate trade and restore banking functionality, the failure to address the IDP crisis threatens to perpetuate a “tent economy” that is humanitarily indefensible and fiscally inefficient over the long term (AWS, 2025). This report evaluates whether the pursuit of monetary sovereignty via redenomination is an essential prerequisite for macroeconomic stability or a costly diversion of capital that could otherwise resolve the housing emergency. The following analysis examines the technical architecture of the proposed currency reform.

Decree No. 293 and Monetary Sovereignty

The transitional government’s decision to replace the Syrian pound is a strategic attempt to reclaim monetary sovereignty and decouple the state’s financial identity from the era of the previous regime (The Syrian Observer, 2026). This reform, codified under Presidential Decree No. 293 of 2025, is not merely a technical adjustment: it is a “soft reset” of the macroeconomic environment designed to simplify transactions in a cash-dependent economy where hyperinflation has rendered daily commerce logistically burdensome (Syria Direct, 2026). By removing two zeros, the government aims to reduce the physical volume of currency required for basic transactions, thereby lowering the friction of commerce.

Aesthetics play a vital role in this transition: the new banknotes replace political portraits with botanical and agricultural symbols (Arab News, 2026). Specifically, the notes feature the Damask rose and olive trees, symbols intended to foster a shared national identity and signal a departure from the previous regime’s cult of personality (Arab News, 2026). However, the aesthetic and symbolic benefits of the new currency carry a significant logistical price tag, placing immense pressure on the Central Bank of Syria (CBS).

Fiscal Logistics and the Liquidity Trap, The Goznak Contract

The CBS, led by Governor Abdulkader Husrieh, is currently navigating a deepening liquidity crisis that has crippled domestic monetary transmission. Approximately 40 trillion Syrian pounds are estimated to be circulating outside the formal financial system, largely in the hands of speculators and remnants of the former regime (Grand Pinnacle Tribune, 2026). This mass hoarding, combined with historical freezes on deposits, has created a parallel “bank balance market” where citizens sell semi-frozen balances at a 25% “haircut” to acquire physical cash (Karam Shaar Advisory, 2026).

The logistical cost of rectifying this system is substantial: a national printing contract for a country of Syria’s scale generally ranges between $200 million and $300 million (Pomeps, 2026). When compared to international benchmarks, such as the United States Federal Reserve’s 2025 currency operating budget of $1.04 billion, the Syrian expenditure appears modest, yet the fiscal context is vastly different (Federal Reserve Board, 2026). The CBS vault reportedly held only $200 million in cash reserves at the time of the 2024 transition, meaning the printing contract with the Russian state-owned firm Goznak represents nearly all available liquid assets of the central authority (Pomeps, 2026).

This Goznak contract represents a zero-sum gamble: the state is essentially purchasing its liquid survival at the expense of northern humanitarian infrastructure. The introduction of the new series acts as a “forced” mechanism to restore the banking sector’s functionality by requiring documentation for large-scale exchanges and proof of origin for sums exceeding certain thresholds (The Syrian Observer, 2026). Failure to produce this fresh supply of currency would likely result in a “liquidity trap,” where degraded banknotes and cash hoarding stifle domestic trade and prevent the disbursement of public sector wages (The Syrian Observer, 2026). This financial imperative stands in direct competition with the escalating humanitarian emergency in the North.

The IDP Shelter Emergency: A Crisis of Displacement and Climate

The humanitarian situation in the northwest governorates of Idlib and Aleppo has reached its most critical level in over a decade during the winter of 2025-2026 (Humanitarian Action, 2026). Extreme weather events, including heavy snowstorms and flooding, have exposed the systemic fragility of the region’s displacement infrastructure, which remains largely reliant on temporary tents (ReliefWeb, 2026).

The following table synthesises the humanitarian metrics from the current winter season:

Humanitarian Metric (Winter 2025/26) | Data Point and Context |

Total IDPs Affected | ~158,000 across Aleppo, Idlib, and Al-Hasakeh (ReliefWeb, 2026) |

Total Households Affected | 21,900 households (ReliefWeb, 2026) |

Total Shelter Damage | ~5,000 tents destroyed or damaged (UN OCHA, 2026) |

Infant Mortality | 2 confirmed deaths: Aqadimi and Tajmuaa Alez sites (ReliefWeb, 2026) |

Heating Fuel Gap | 100% gap in Al-Hasakeh and Ar-Raqqa shelters (UN OCHA, 2026) |

Winter Aid Funding Gap | 72% – 74% as of January 2026 (ReliefWeb, 2026) |

The current “tent-cycle” model is failing: temporary shelters provide inadequate insulation, leading to lethal hypothermia and a surge in respiratory illnesses (ReliefWeb, 2026). In the first two days of 2026, the human cost was made clear by the deaths of a two-day-old girl at the Aqadimi site and a three-month-old boy at the Tajmuaa Alez site (ReliefWeb, 2026). These tents fail to provide the “dignified” standard required for long-term stability, as they lack privacy and integrated sanitation, which increases protection risks and the incidence of communicable diseases (AWS, 2025). The transition to durable housing is no longer just a humanitarian preference: it is a fiscal necessity to end the recurring costs of emergency aid.

Unit Cost Analysis: From “Tent-Cycle” to Durable Assets

Transitioning from temporary tents to durable housing requires a higher upfront investment but offers a vastly superior value-for-money proposition over a multi-year horizon (AWS, 2025). A standard tent costs $800 but must be replaced every six to twelve months due to environmental degradation, whereas a durable shelter has a lifespan exceeding ten years (AWS, 2025).

A comparison of the various housing models available in Northern Syria is provided below:

Housing Model Type | Est. Unit Cost (USD) | Specifications |

Standard Tent | $800 – $850 | 16 sq-m, 6-12 month lifespan (AWS, 2025) |

Brick House | $1,500 – $1,600 | 38 sq-m, 2 rooms, kitchen, washroom (Muslim Hands UK, 2021) |

Dignified Shelter (UNHCR) | $2,900 | 2 rooms, kitchen, bath, basic infra (AWS, 2025) |

Residential Village Apartment | $12,500 | Fully furnished, solar, schools, mosques (Doha News, 2026) |

The fiscal efficiency of durable housing is underscored by the “avoided cost” of the tent model. Over a five-year horizon, the total expenditure for a family in a tent, including replacements and winterisation, reaches approximately $7,100 (AWS, 2025). In contrast, the “Dignified Shelter” model costs only $2,900 over the same period, making it 59% more cost-effective (AWS, 2025). This stark difference highlights the significant opportunity cost of the current fiscal priorities.

Opportunity Cost Analysis: Modelling the $250 Million Trade-off

The central policy trade-off for the transitional government involves comparing the utility of the $250 million earmarked for banknote production against its potential application in the housing sector. This $250 million represents a massive foregone opportunity to stabilise the displaced population. Using the budgetary figure of L = 250,000,000, we can model the housing capacity:

- Dignified Shelters: The budget could fund approximately 86,206 units.

- Brick Houses: The budget could fund approximately 166,666 units.

Given an average family size of five, redirecting this budget could permanently rehouse between 431,000 and 833,000 people, representing 25% to 50% of the entire tent-dwelling population in Northern Syria (Islamic Relief SA, 2026). Furthermore, the currency budget could cover the $112 million winter aid appeal three times over, a critical fact given that the appeal currently faces an $81 million funding gap (ReliefWeb, 2026).

These investments are further complicated by the cost of capital in a post-conflict environment. The CBS has set the rediscount rate at 5.00% as of December 2025, but foreign investors face risk premiums and annual insurance rates ranging from 15% to 25% (Karam Shaar Advisory, 2026). These high capital costs create a “hurdle rate” that humanitarian projects cannot meet without state subsidies, making the potential redirection of state funds even more vital. However, legal and logistical barriers remain significant impediments to a simple redirection of capital.

HLP Rights and Explosive Ordnance

Even if funds were redirected, the implementation of mass rehousing faces a “vast legal and bureaucratic arsenal” left by the previous regime (PAX, 2025). Law No. 10 of 2018, which allowed for property confiscations under the guise of redevelopment, remains a primary barrier (PAX, 2025). Approximately 70% of displaced persons lack proper documentation, and many IDP sites are located on private or communal (“Musha”) land with unverified ownership (PAX, 2025; ACHR, 2026). Constructing permanent housing without a robust restitution framework risks “whitewashing” past human rights violations by cementing the results of displacement (PAX, 2025).

The risk of whitewashing is particularly acute when permanent assets are created on land that may have been illegally expropriated from original owners who are now refugees or IDPs themselves. Without a national framework for restitution, these housing projects could inadvertently validate the previous regime’s demographic engineering. Security risks also present a lethal challenge: the presence of Explosive Ordnance (EO) has led to casualty rates doubling between 2024 and 2025 (Humanitarian Action, 2026). Crucially, 60% of EO incidents occur in agricultural areas that are slated for housing development, necessitating expensive and time-consuming demining operations before construction can begin (Humanitarian Action, 2026). These factors suggest that while the capital is available, the environment for its deployment remains fractured.

Sectoral Comparison, Public Health vs. Macroeconomic Stability

The trade-off between fiscal tools and physical infrastructure is multi-dimensional. On one hand, the transition to durable housing offers immediate public health benefits: it reduces chronic respiratory illness, eliminates the dampness and mold of polymer tents, and restores privacy, which is essential for reducing protection risks like gender-based violence (ReliefWeb, 2026; AWS, 2025). The fiscal multiplier of housing is also significant, as it creates local construction jobs and reduces the recurring expenditure on emergency aid that currently dominates the northern economy (AWS, 2025).

On the other hand, the new currency supply provides macroeconomic foundations. It reduces transaction costs by replacing degraded notes and potentially ends the predatory “haircut” market by restoring liquidity to the banking sector (Karam Shaar Advisory, 2026). However, redenomination carries the risk of “money illusion,” a cognitive bias where the public focuses on lower nominal values rather than real purchasing power (Modern Diplomacy, 2025). If transparency is not maintained, this may lead to sub-optimal domestic spending or a failure to address the underlying drivers of inflation. Ultimately, the state requires both a functional medium of exchange and a healthy, sheltered population to achieve long-term sovereign solvency.

Synthesis and Strategic Recommendations

A complete cancellation of the currency project is likely unfeasible, as it would lead to hyper-dollarisation and a total loss of independent monetary policy (The Syrian Observer, 2026). However, a “Hybrid Policy” of re-prioritisation is both feasible and necessary. By focusing only on high-denomination notes, the CBS could save between $100 million and $150 million in printing costs, as printing a smaller number of high-value bills is more cost-effective than a full spectrum of small-denomination notes (Al-Estiklal, 2026; Pomeps, 2026).

The following table compares the potential policy paths:

Policy Path | Economic Outcome | Humanitarian Outcome |

Status Quo: Full Swap | Restored liquidity: high fiscal cost (The Syrian Observer, 2026). | Continued “tent-cycle”: high recurring costs (AWS, 2025). |

Partial Shift: High-Denom | Solves large deals: saves ~100M-150M (Al-Estiklal, 2026). | Redirects funds to house ~35,000 families (AWS, 2025). |

Full Shift: Housing | Risks monetary collapse: dollarisation (The Syrian Observer, 2026). | Ends tent crisis for ~160,000 families (Islamic Relief SA, 2026). |

It is recommended that the transitional government establish a state-backed “Housing for Dignity” fund. This fund should target the 81,520 families currently residing in sites where Housing, Land, and Property (HLP) rights have already been validated by local councils, thereby bypassing the most complex legal obstacles (AWS, 2025). Syria’s stability in 2026 depends on the transition from an emergency-based “tent economy” to a durable “brick economy.” If the state prints new notes while its children continue to freeze in tents, the new currency will lack the most vital security feature: public trust in the state’s legitimacy (Modern Diplomacy, 2025).

References

- ACHR (2026) وصول. Available at: https://achrights.org/en/2026/01/20/16188/

- Al Arabiya (2026) Syria to start currency swap on January 1, central bank governor says. Available at: https://english.alarabiya.net/business/economy/2025/12/25/syria-to-start-currency-swap-on-january-1-central-bank-governor-says

- Al-Estiklal (2026) Dropping Zeros from the Syrian Pound: Political Move or Economic Gain?. Available at: https://www.alestiklal.net/en/article/cutting-zeros-from-the-syrian-pound-political-move-or-economic-gain

- Al-Estiklal (2026) Syria Cuts Two Zeros from Its Currency: Smart Move or Dangerous Bet?. Available at: https://www.alestiklal.net/en/article/syria-cuts-two-zeros-from-its-currency-smart-move-or-dangerous-bet

- Arab News (2026) Syria begins circulating new post-Assad currency bills. Available at: https://www.arabnews.jp/en/middle-east/article_161762/

- AUB (2026) Housing, land and property rights: a main determinant for syrian potential returnees. Available at: https://www.aub.edu.lb/ifi/Documents/Housing-Land-and-Property-Rights-A-Main-Determinant-for-Syrian-Potential-Returnees.pdf

- AWS (2025) Action Plan for Dignified Shelter & Living Conditions in North-West Syria. Available at: https://unhcr-sheltercluster-static.s3.eu-west-1.amazonaws.com/public/docs/Action%20Plan%20for%20Dignified%20Shelter%20%26%20Living%20Conditions%20in%20NW%20Syria_Draft_v5_0.pdf

- Doha News (2026) Qatar Charity begins work on ‘largest housing projects’ for displaced Syrians. Available at: https://dohanews.co/qatar-charity-begins-work-on-largest-housing-projects-for-displaced-syrians/

- Federal Reserve Board (2026) How much does it cost to produce currency and coin?. Available at: https://www.federalreserve.gov/faqs/currency_12771.htm

- Grand Pinnacle Tribune (2026) Syria Moves To Drop Two Zeros From Currency. Available at: https://evrimagaci.org/gpt/syria-moves-to-drop-two-zeros-from-currency-493831

- Grand Pinnacle Tribune (2026) Syria To Remove Two Zeros From Pound In December. Available at: https://evrimagaci.org/gpt/syria-to-remove-two-zeros-from-pound-in-december-493145

- HPC (2026) Provision of essential non-food items and shelter assistance to most vulnerable families in north-west Syria. Available at: https://projects.hpc.tools/project/164756/view

- HPC (2026) Shelter, NFI and winterization assistance for the most vulnerable men, women, boys and girls in NW Syria. Available at: https://projects.hpc.tools/project/211904/view

- House of Commons Library (2026) Syria one year after Assad: Forming an interim government. Available at: https://commonslibrary.parliament.uk/research-briefings/cbp-10430/

- Humanitarian Action (2026) Syrian Arab Republic | Global Humanitarian Overview 2026. Available at: https://humanitarianaction.info/document/global-humanitarian-overview-2026/article/syrian-arab-republic-4

- IOM (2026) Syrian Arab Republic Crisis Response Plan 2026. Available at: https://crisisresponse.iom.int/response/syrian-arab-republic-crisis-response-plan-2026

- Islamic Relief SA (2026) Build homes for Syrian families. Available at: https://islamic-relief.org.za/build-homes-for-syrian-families/

- Karam Shaar Advisory (2026) New Banknotes for a New Syria: Rebuilding Trust and Restoring Faith in the Pound. Available at: https://karamshaar.com/syria-in-figures/new-banknotes-for-a-new-syria-rebuilding-trust-and-restoring-faith-in-the-pound/

- Karam Shaar Advisory (2026) Syria Banking Crisis 2025: Frozen Deposits & Parallel Market. Available at: https://karamshaar.com/syria-in-figures/syria-banking-crisis-2025/

- Karam Shaar Advisory (2026) Syria Sanctions Monitor: Issue 5. Available at: https://karamshaar.com/sanctions_program/syria-sanctions-monitor-issue-5/

- Liga.net (2026) Syria to revalue currency: new bills without two zeros to be issued by Russian company. Available at: https://finance.liga.net/en/ekonomika/novosti/syria-to-revalue-currency-new-bills-without-two-zeros-to-be-issued-by-russian-company-reuters

- Modern Diplomacy (2025) Syrian Central Bank Announces New Currency, Swap to Begin in 2026. Available at: https://moderndiplomacy.eu/2025/12/25/syrian-central-bank-announces-new-currency-swap-to-begin-in-2026/

- Muslim Hands UK (2021) Press Release: 150 Houses for Displaced Syrian Families. Available at: https://muslimhands.org.uk/latest/2021/02/press-release-building-houses-for-syrian-families-in-idlib

- NRC (2026) BRIEFING NOTE: HOUSING LAND AND PROPERTY (HLP) IN THE SYRIAN ARAB REPUBLIC. Available at: https://www.nrc.no/globalassets/pdf/reports/housing-land-and-property-hlp-in-the-syrian-arab-republic.pdf

- OHCHR (2026) Syrian Legal Development Programme. Available at: https://www.ohchr.org/sites/default/files/documents/issues/housing/cfis/cfi-land/subm-land-adequate-housing-cso-27-syrian-legal-development-programme.docx

- PAX (2025) The Struggle for HLP rights in Post-Assad Syria. Available at: https://paxforpeace.nl/wp-content/uploads/sites/2/2025/09/PAX_Syria-Report_Reclaiming-What-Was-Taken_v1.4.pdf

- Pomeps (2026) The Pound in the Post-Assad Era: Currency Stabilization in Syria. Available at: https://pomeps.org/the-pound-in-the-post-assad-era-currency-stabilization-in-syria

- ReliefWeb (2026) North-West Syria – Flooding in Displacement Camps. Available at: https://reliefweb.int/report/syrian-arab-republic/north-west-syria-flooding-displacement-camps-dg-echo-dg-echo-partners-un-ocha-media-echo-daily-flash-21-january-2026

- ReliefWeb (2026) Project to Build 2,200 Clay Houses for Syrian IDPs. Available at: https://reliefweb.int/report/syrian-arab-republic/project-build-2200-clay-houses-syrian-idps

- ReliefWeb (2026) Qatar Charity completes first phase of housing project for Syrian IDPs. Available at: https://reliefweb.int/report/syrian-arab-republic/qatar-charity-completes-first-phase-housing-project-syrian-idps

- ReliefWeb (2026) Qatar Charity constructs homes for Yemen’s IDPs. Available at: https://reliefweb.int/report/yemen/qatar-charity-constructs-homes-yemens-idps-enar

- ReliefWeb (2026) QRCS completes furnishing, infrastructure for residential villages of northern Syria. Available at: https://reliefweb.int/report/syrian-arab-republic/qrcs-completes-furnishing-infrastructure-residential-villages-northern-syria-enar

- ReliefWeb (2026) Syria: Cold Wave – Dec 2025. Available at: https://reliefweb.int/disaster/cw-2025-000226-syr

- ReliefWeb (2026) Syrian Arab Republic: Flash Update No. 2 – Second Winterstorm Hits Communities in Syria. Available at: https://reliefweb.int/report/syrian-arab-republic/syrian-arab-republic-flash-update-no-2-second-winterstorm-hits-communities-syria-26-january-2026-enar

- ReliefWeb (2026) Housing, Land and Property (HLP) Technical Working Group Syria – Terms of Reference. Available at: https://reliefweb.int/report/syrian-arab-republic/housing-land-and-property-hlp-technical-working-group-syria-terms-reference

- ResearchGate (2026) Production Cost Function for Banknote Printing Industry. Available at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/340173996_Production_Cost_Function_for_Banknote_Printing_Industry

- Russia’s Pivot to Asia (2026) Russia To Print New Syrian Banknotes. Available at: https://russiaspivottoasia.com/russia-to-print-new-syrian-banknotes

- SANA (2026) Presidential decree launches new Syrian currency starting 2026. Available at: https://sana.sy/en/presidency/2286703/

- STJ (2020) Violations of Housing, Land and Property Rights: An Obstacle to Peace in Syria. Available at: https://stj-sy.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/PolicyBrief_Syria_HLP_2020_eng.pdf

- Syria Accountability (2025) A Roadmap for Transitional Justice in Syria – September 2025. Available at: https://syriaaccountability.org/a-roadmap-for-transitional-justice-in-syria-september-2025/

- Syria Direct (2026) Deleting zeros: Will Syria’s new currency lighten the load, or add confusion?. Available at: https://syriadirect.org/deleting-zeros-will-syrias-new-currency-lighten-the-load-or-add-confusion/

- Syrian Guides (2026) Syria launches the new Syrian pound in 2026. Available at: https://syrianguides.com/syria-launches-the-new-syrian-pound-in-2026/

- The National (2025) Success of Syria’s new currency move will rely more on ‘policy than new notes’. Available at: https://www.thenationalnews.com/business/economy/2025/08/26/success-of-syrias-new-currency-move-will-rely-more-on-policy-than-new-notes/

- The Syrian Observer (2026) Housing Takes a Backseat in Syria Amid Economic Turmoil. Available at: https://syrianobserver.com/society/housing-takes-a-backseat-in-syria-amid-economic-turmoil.html

- The Syrian Observer (2026) Is Goznak a Suitable Choice for Printing the Syrian Currency?. Available at: https://syrianobserver.com/foreign-actors/is-goznak-a-suitable-choice-for-printing-the-syrian-currency.html

- The Syrian Observer (2026) Syria’s Liquidity Crisis: Causes, Solutions, and Economic Priorities. Available at: https://syrianobserver.com/society/syrias-liquidity-crisis-causes-solutions-and-economic-priorities.html

- The Syrian Observer (2026) Syria’s New Currency: A Financial Battle for Economic Sovereignty. Available at: https://syrianobserver.com/society/syrias-new-currency-a-financial-battle-for-economic-sovereignty.html

- The Times of Israel (2026) Syria to revalue currency, dropping two zeros in bid for stability. Available at: https://www.timesofisrael.com/syria-to-revalue-currency-dropping-two-zeros-in-bid-for-stability/

- TRT World (2026) Explained: Syria’s currency revaluation and how it works. Available at: https://www.trtworld.com/article/b59c4b988084

- UN OCHA (2026) Syrian Arab Republic: Flash Update No. 1 – Heavy Snowfall Hits Displaced Communities in Northern Syria. Available at: https://www.unocha.org/publications/report/syrian-arab-republic/syrian-arab-republic-flash-update-no-1-heavy-snowfall-hits-displaced-communities-northern-syria-6-january-2026

- UNHCR (2024) Annual Results Report – 2024 Syrian Arab Republic. Available at: https://www.unhcr.org/sites/default/files/2025-06/Syrian%20Arab%20Republic%20ARR%202024.pdf

- Xinhua (2025) Syria unveils currency reform plan, cutting 2 zeros from pound. Available at: https://english.news.cn/20251229/192c5a92ad34493d88cecd075a8b6301/c.html